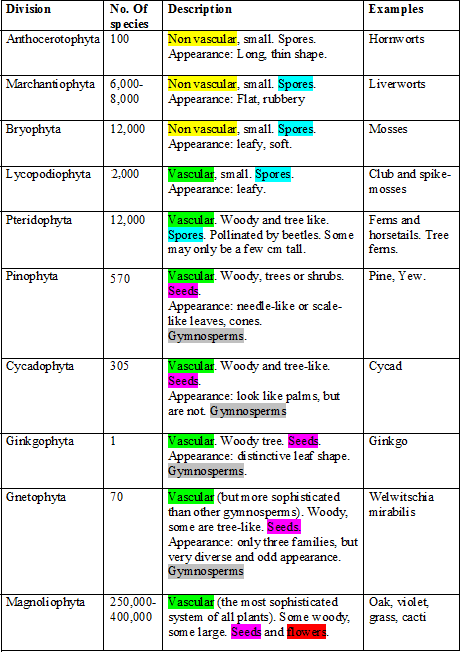

A Few Basic Facts

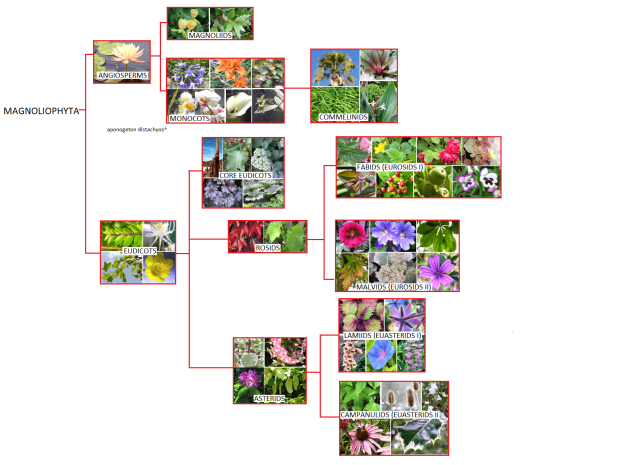

- Aroids are monocots in the family Araceae (aka arum family), in the order Alismatales. Most other families in this order contain tropical or aquatic plants, eg Hydrocharis and Saggitaria.

- Araceae has 104-107 genera. The largest genus is Anthurium with over 700 species.

- Location: Latin American tropical regions have the greatest diversity of aroids, however, they can also be found in Asia and Europe. Australia has only one endemic species – Gymnostachys.

- Habitat: Aroids can be aquatic (water), epiphytic (air) and terrestrial (ground). Most are tropical, but there are also arid and cold loving aroids.

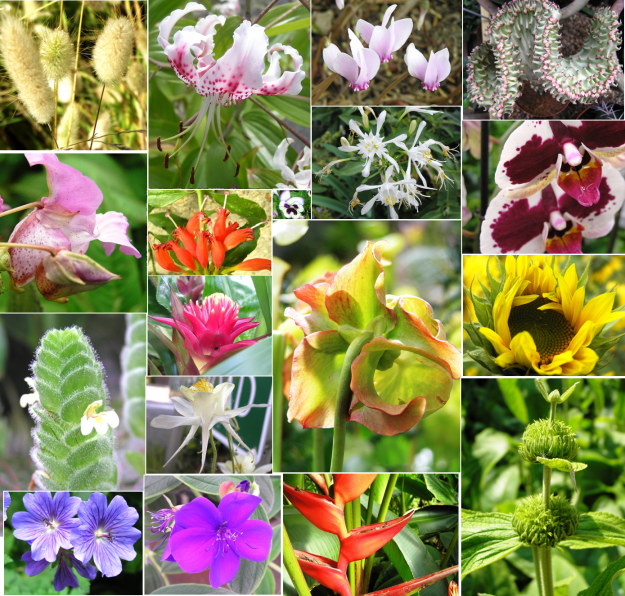

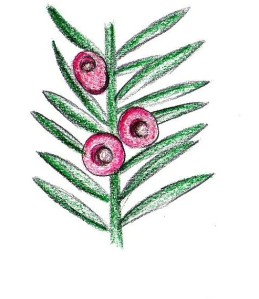

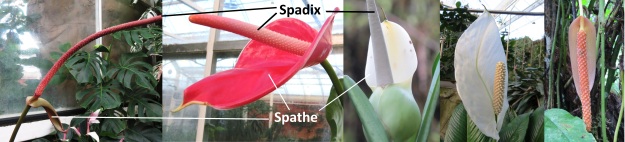

- Distinctive features: All have an inflorescence (a structure containing a group of smaller flowers) which consists of a spadix (always) and a spathe (sometimes).

Aroid Flowers

- Aroids can be hermaphrodite (each flower is both male and female), monoecious (male and female flowers on the same spadix) or dioecious (male and female flowers on completely different plants).

- This family contains one of the largest flowers (Amorphophallus titanium, the titan arum) and the smallest (Wolffia, duckweed).

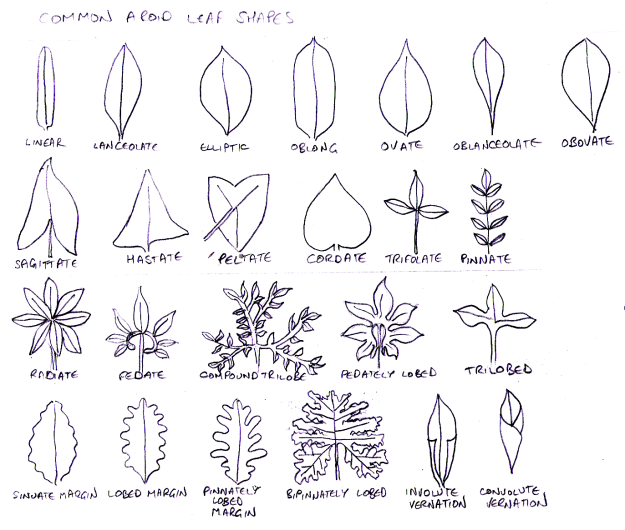

- Some aroid leaf and inflorescence shapes:

Aroid Leaves

Aroid Fruits

Adaptations

Like many tropical families, aroids have evolved a number of adaptations to stay healthy and propagate. Some examples of adaptation:

- The spathe protects the flowers and in some cases is used to trap insects for pollination. It is not a petal, but a modified leaf. Many spathes turn green and photosynthesize after flowering has finished.

- Aroids have different types of roots adapted to their purpose. They have different adventitious roots for climbing, attaching to rocks or taking in water.

- Many tropical species have shiny leaves to deter the mosses and lichens that grow in abundance in the rainforest.

- Smell is used by many species to attract pollinators. The smell of rotting meat, fungi and excrement is used for flies and beetles. Fragrant scents are used to attract bees.

- In many species the spadix actually heats up and can reach 25°C, even in near freezing conditions. This increases the release of smells to attract pollinators. The heat also makes visiting insects more active.

- Aroids that want to attract flies and beetles often have a warty, hairy, twisted appearance, with dark colours. This is to mimic the effect of dead animals, fungi or excrement.

- In some species, leaves may change shape from juvenility to adulthood – changing from variegated to unvariegated, pale red to green, or altering the number of lobes of the leaf. Colour change may deter animals from feasting on the fresh young leaves by making them look less leaf-like.

- Most species in Araceae have tubers or rhizomes, this means a damaged plant has the food storage and ability to grow new shoots from many points beneath the ground. Some aroids have other means of vegetatively propagating themselves, such as bubils and offsets.

- A number of aroids are poisonous, some are edible. Aroids have evolved poisons in some species as protection. Those that are edible did not evolve to be eaten by us, rather we have evolved to be able to eat certain plants.

Reproduction

Male and Female Flowers

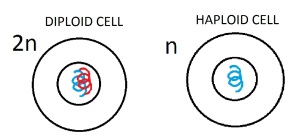

Because many aroids are monoecious there is a danger of self-pollination. While self-pollination is easy (a guaranteed fertilisation), it leads to less genetic variety and less ability to adapt to changes in the environment. Aroids are particularly variable plants, in one small area of the Thai Peninsula 22 distinct varieties of the plant Aglaonaemia nitidum f. curtisii were found. However, in order to achieve this variation, the plant needs to cross pollinate reliably. It does this by being protogynous, meaning the female flowers on an inflorescence ripen first and then later male flowers produce pollen.

The Generic Process for Monoecious Aroids

A beetle, fly or bee (hopefully covered in pollen) is attracted by the scent given off by the heated spadix. The insect flies around inside the spathe, lands on the slippery surface and falls into the gap between the spadix and spathe. At this point only the female flowers are mature, and the insect, made more active by heat from the spadix, moves about bumping into the flowers and depositing the pollen. Now, the insect has fulfilled the first part of its function, the aroid would like it to pick up pollen from the male flowers. However, the male flowers will not ripen for a day or so yet, so the insect needs to be held hostage. The slippery spathe ensures that the insect can’t escape, it is given sustenance in the form of nectar. Once the male flowers are ready and producing pollen, the slippery surface of the spathe breaks down, allowing the insect to escape. As it flies away it bumps into the male flowers, picking up more pollen to take to the next plant of the same species that it comes to.

Two Specific Examples of Monoecious Reproduction

Philodendron auminatissimum: Sometimes the pollinating insect can outstay its welcome, perhaps damaging flowers or laying eggs. This Philodendron has overcome the problem by shrinking the spathe after the male flowers have become active. This means that the beetle must leave or become crushed.

Arum nigrum: This arum doesn’t trap visiting flies, it merely confuses them. The hood of the spathe hangs over the spadix, obscuring the sunlight, and there are translucent marking in the base of the spathe. When a visiting fly tries to escape, it heads for the light, but this just guides it deeper into the spathe. This leads to panicked and more active movement, ensuring pollination.

Arum nigrum

Reproduction in Other Aroids

In dioecious aroids the female flowers are found on a different plant to the male flowers, so a genetic mix is guaranteed. Not many aroids are dioecious, but a few species of Arisaema are.

A few aroids are even paradioecious and change gender to suit circumstances.

Hermaphrodite aroids are similar to monoecious ones, the male and female parts on each flower mature at different times so self pollination cannot occur.

Habitat

Arid

For the most part, arid aroids have not evolved the typical shrunken leaves and thickened cuticle of other desert plants. Instead they tend to grow under trees and bushes and at the base of rocks where a damp, shady microclimate allows them to survive. They have unusually lush foliage for arid plants. This would make them a target for being eaten, but they have dealt with this by producing harsh toxins and needles of calcium oxalate that pierce and poison the throats of animals. Animals know to stay well clear of aroids.

Some Examples

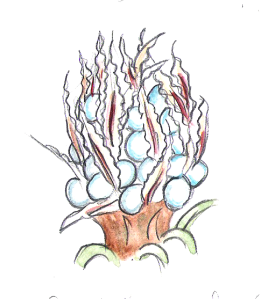

Heliocodicerous muscivorus

Heliocodicerous muscivorus: This is called the dead horse arum. It has an inflorescence 35cm long and wide. It grows in the shelter of rocks on a few islands on the Mediterranean. It is pollinated by either flies or beetles and grows where sea birds have their colonies at nesting time. Sea birds live in a mess of rotting fish and eggs, dead chicks and excrement, which attracts the flies/beetles. The arum must then compete with the smell of these, in order to attract those same insects for pollination. It mimics the dead not only in smell, but also by looking like the corpse of part of a horse, complete with tail. Visiting insects find themselves falling into where the ‘tail’ is and becoming trapped by the slippery walls. Many insects lay their eggs inside, although any maggots that hatch will likely starve to death. The insects are held for two to three days and are fed by nectar.

Note: It’s worth looking at photos of the dead horse arum, my painting doesn’t really do it justice.

Sauromatum venosum: This is the called the voodoo lily because it has the ability to flower without soil or water, using only the energy stored as starch in the corm. It smells rotten.

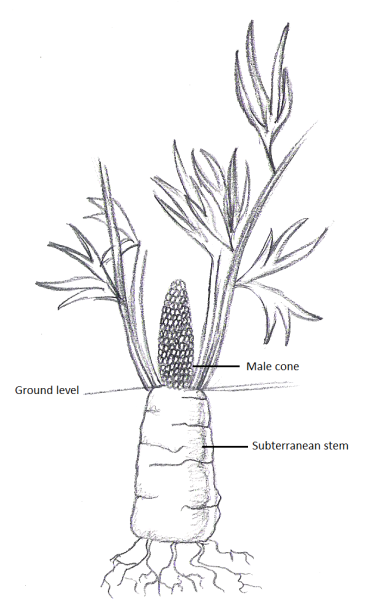

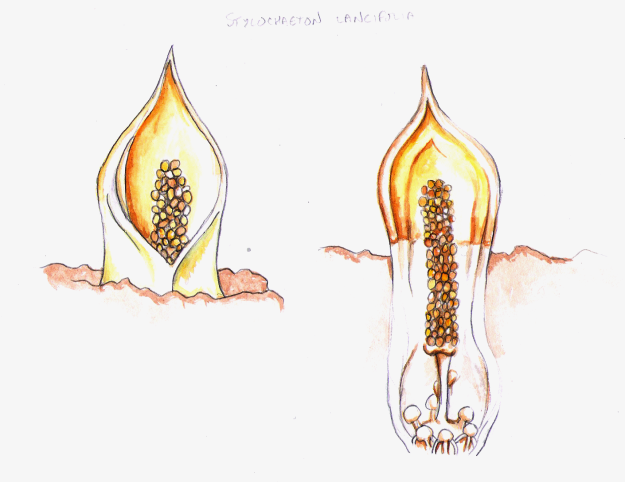

Stylochaeton lancifolius: This aroid has flowers and fruits half buried in the ground. I have been unable to find information about why this is. My suspicions are:

- It is pollinated by animals that are close to the ground. This can be seen in Aspidistra flowers, pollinated by slugs and snails. The flowers grow on the ground, under the leaves.

- Being submerged provides a little protection, even if eaten or stepped on, the Stylochaeton still has half a flower remaining.

- The fruits are eaten by something small. Having eaten the fruit, the seeds can be dispersed in the faeces.

Stylochaeton lancifolia

Tropical

Rainforests are dense, shady, and teeming with aggressive life. Animals, plants, fungi and bacteria are locked in a constant arms race. Consequently aroids have developed strong poisons, shiny leaves and the ability to climb to cope with some of these problems. In the tropics, latitudinal diversity (a wider variety of organisms that occurs close to the equator) means that it may be many miles through dense forest between plants of the same species. For this reason, aroids use very strong, and often unpleasant, smells to attract the right kind of insect.

A tropical rainforest has distinct layers and aroids grow in each of these. There are terrestrial aroids growing in the ground and epiphytic ones that climb into the canopy.

Climbers and epiphytes have only aerial, adventitious roots. There are two types: those that are sensitive to light and make for dark crevices where they can grip, and those that are sensitive to gravity and hang down from the plant in order to soak up rain and humidity.

Terrestrial Examples

Deiffenbachia grows in the Americas, while Aglaonema is native to Asia, they are both highly variable, but virtually indistinguishable from one another. This is an example of convergent evolution. Both contain toxins as a defence; Deiffenbachia is commonly known as dumb cane, because the if eaten, it causes the throat to swell, so that speech is impossible.

Aglaonema and Deiffenbachia – both highly variable, but in similar ways

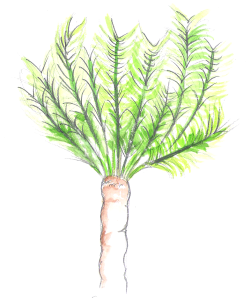

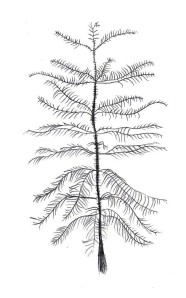

Amorphophallus: This is a genus of tropical and subtropical aroids, native to Asia, Africa and Australasia. They attract flies and beetles by giving off the smell of rotting meat. Unusually, Amorphophallus species only put out one leaf or one inflorescence at a time, one a year. The single leaf is highly divided.

Some Amorphophallus inflorescences

Single, highly divided leaf of Amorphophallus

Some species in this genus also have white patches on the stem, these are to mimic lichen growing on trees and serve to protect them from stampeding elephants. When tramping through the jungle elephants have learnt to avoid trees, which are usually covered in lichen. Amorphophallus would be very easily damaged by an elephant, so by looking a bit more like a tree they can fool the elephant into avoiding them.

Lichen mimicking stem

Epiphytic Examples

Monstera

Monstera: These are one of the few plants to have holes in their leaves. Recent research shows that leaves with holes benefit in shady areas because the light coming through the trees is often dappled. By having holes in their leaves, Monstera cover a larger area with the same amount of leaf (so the same amount of energy used to make it) as a smaller leaf without holes. This allows the plant to take advantage of any sunlight that gets through the canopy.

Anthurium punctatum: This is an aroid from Ecuador. It has formed a symbiotic relationship with ants. It has nectaries away from the flowers because it is not trying to attract pollinators, but protectors. The ants set up home in the Anthurium and guard it from animals and insects that may eat it. However, in this Anthurium the ants are particularly aggressive and keep away pollinators also. The ants also secrete an antibiotic substance called myrmiacin, which is antibiotic and protects the ants from moulds and bacteria that might cause disease. However, this substance prevents pollen tube formation needed for the plant to be fertilised. These two barriers to pollination mean that the species can only propagate itself vegetatively.

Philodendron: This is a diverse genus. Plants can be epiphytic, hemiephytic or (occasionally) terrestrial. Hemiepiphytic means that the plant spends part of its life-cycle as an epiphyte (in the air). It may start off on the ground and then wind its way up a tree, then let its original roots die back. Or it may start as a seedling in the branches of a tree and a root will trail its way to the ground.

Philodendron bipinnatifidum

Temperate Woodland

Arisarum proboscideum

Arisarum proboscideum: aka the mouse plant. This is a woodland aroid, native to Spain and Italy. It has flowers like little mice. The ‘tails’ of these give off a mushroomy odor, that attract fungus gnats for pollination. The flowers have a spongy white appendage inside the spadix that looks like a mushroom to complete the deception. Fungus gnats often lay their eggs in the flowers, although the maggots won’t live to adulthood.

Aquatic

As I have blogged before, plants never evolved much in water. This means that all aquatic plants have evolved on land and then evolved again to cope with life in water. Some problems faced are – damage to flowers and leaves due to water currents, lack of access to pollinators, water blocking out light, lack of oxygen (leading to rotting roots), and the heaviness of water (800 times as dense as air) putting pressure on foliage.

Some solutions to problems:

- Aerenchyma: these are gas filled cavities that improve buoyancy and oxygenation.

- Fish shaped foliage: these offer less resistance to water currents, so less damage occurs.

- Larger surface area in relation to volume: ie filmy leaves. This increases photosynthesis eg Cryptocoryne

- Roots: These are not needed to transport water, since it can be taken in by all parts of the plant. However, roots are used to anchor the plant and stopped it being carried away by currents. eg Jasarum steyermarkii

- Reproduction: Many aquatic aroids find it easier to spread vegetatively rather than by flowering, in order to avoid flowering problems.

An Example

Pistia stratiotes: This is the only floating aquatic aroid, growing in swampy deltas in India and West Africa. It is adapted to staying still in fast moving currents, and has found the balance between sinking and blowing away. The inner tissues have aerenchyma and the outer surfaces are ridged, velvety and with dense covering of hairs. This makes it unable to sink, and water repellent. Feathery roots act as an anchor. It has tiny flowers in a protective hairy spathe.

Pistias form a dense mat on the surface of the water, and can create mats of 15m wide. This makes Pistia something of a weed, causing problems to the ecosystem because the water underneath is deprived of light.

However, Pistia is not only harmful, some ecological benefits:

- The darkness caused by the Pistia mats has led to the evolution of blind elephantnose fish, which live beneath the mats. They hunt by electricity and have well developed brains and learning abilities.

- Birds and animals often make the floating island their home.

- Pistia can purify stagnant water.

Note: outdoor photos are mostly taken in Ecuador and indoor photos mostly from Wisley Gardens.